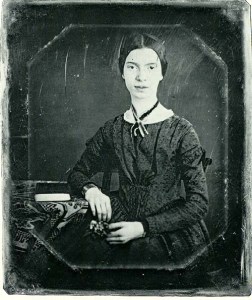

‘I had been hungry, all the Years’ is one of hundreds of poems Emily Dickinson wrote but never published. (As we’ve previously noted, when she died she was far better-known as a gardener than as a poet.) ‘I had been hungry, all the Years’ uses hunger and food as metaphors, a way to explore other themes, much as Dickinson does elsewhere (such as when she compares fame to food).

I had been hungry, all the Years –

My Noon had Come – to dine –

I trembling drew the Table near –

And touched the Curious Wine –

’Twas this on Tables I had seen –

When turning, hungry, Home

I looked in Windows, for the Wealth

I could not hope – for Mine –

I did not know the ample Bread –

’Twas so unlike the Crumb

The Birds and I, had often shared

In Nature’s – Dining Room –

The Plenty hurt me – ’twas so new –

Myself felt ill – and odd –

As Berry – of a Mountain Bush –

Transplanted – to a Road –

Nor was I hungry – so I found

That Hunger – was a way

Of Persons outside Windows –

The Entering – takes away –

You can wait so long for something you earnestly desire that, when you finally attain it, it doesn’t bring the fulfilment you hoped and thought it would. The ‘something’ here can be any number of things – wealth, love, that job you  always wanted, the validation of someone you admire.

always wanted, the validation of someone you admire.

The beauty of Emily Dickinson’s poem is that she uses hunger and feasting as metaphors that can be related to many different life experiences.

The wine is ‘curious’ and the bread is ‘ample’, but she hasn’t the stomach for them: they’ve come too late for her to get the full enjoyment of them. ‘The Plenty hurt me – ’twas so new – / Myself felt ill – and odd’.

Dickinson’s poem effectively says what cognitive science is now proving: that happiness, to quote another female writer, Diana Wynne Jones, ‘isn’t a thing. You can’t go out and get it like a cup of tea. It’s the way you feel about things.’

Lottery winners may wake up the day after they win the £10 million jackpot and pinch their arms and say over and over how they can’t believe their luck, but in time, their mood, their state of being, will settle back down to how it was before they had their millions.

If the ‘window’ separating the speaker from her former life (when she was, to quote from James Joyce, ‘outcast from life’s feast’) and the life of ‘plenty’ which she eyes enviously from afar is meant to summon the gulf between the ‘Haves’ and ‘Have-Nots’, the difference between rich and poor, then it is not reducible to only this interpretation: when we analyse Dickinson’s use of nature imagery, the poem becomes richer (as it were) and more complex than a simple lesson in class differences.

Look at how the speaker shared her ‘crumb’ with the birds, while that berry which is ‘transplanted’ from its natural habitat of a mountain bush to a road (an artificial, man-made structure) is thus taken out of its natural surroundings. (‘Transplanted’ is exactly the right word, too, with ‘plant’ summoning the world of nature that bore the berry, and ‘transplanted’ suggesting human interception.)

Is wealth and plenty all it’s cracked up to be? Or is this, as Anna Letitia Barbauld suggests in her satirical poem ‘To the Poor’, merely what the Haves tell the Have-Nots to keep them in their place?

If you enjoyed ‘I had been hungry, all the Years’ and found our analysis helpful, we’ve analysed and shared more of Dickinson’s finest poetry here.

I almost used this poem in a post recently – so smoked to see it here …

Every time I come across a poem by Emily Dickinson I haven’t read before, my hearts swells further in respect for that solitary poet.

She’s brilliant, isn’t she? She was prolific, but wrote about a great range of things, and had such a unique eye for detail.