A summary of a classic Dickinson poem by Dr Oliver Tearle

‘One need not be a Chamber – to be Haunted’. So begins one of Emily Dickinson’s most striking poems. This poem requires close analysis because it presents an interesting nineteenth-century example of the internalisation of ‘spirits’ and the notion of ‘haunting’.

One need not be a Chamber—to be Haunted—

One need not be a House—

The Brain has Corridors—surpassing

Material Place—

Far safer, of a Midnight Meeting

External Ghost

Than its interior Confronting—

That Cooler Host.

Far safer, through an Abbey gallop,

The Stones a’chase—

Than Unarmed, one’s a’self encounter—

In lonesome Place—

Ourself behind ourself, concealed—

Should startle most—

Assassin hid in our Apartment

Be Horror’s least.

The Body—borrows a Revolver—

He bolts the Door—

O’erlooking a superior spectre—

Or More—

As that eye-catching opening line makes clear, ‘One need not be a Chamber – to be Haunted’ is about how the real ghosts, the ones we should really fear, are to be found within our own minds. In summary, we should fear our own  thoughts and fears rather than the supposed presence of any external being, or the ‘Assassin hid in our Apartment’. Forget about haunted houses or ghostly horses heard in old abbeys; the real terror is to be found within ourselves.

thoughts and fears rather than the supposed presence of any external being, or the ‘Assassin hid in our Apartment’. Forget about haunted houses or ghostly horses heard in old abbeys; the real terror is to be found within ourselves.

Emily Dickinson was writing before Freud, and yet the idea of an ‘Ourself behind ourself, concealed’, which should startle us the most, anticipates the notion that we have multiple selves, and parts of our own minds which we scarcely understand (what Freud theorised as the ‘unconscious’, where our true desires and fears were located, largely hidden from us). Encountering yourself in a ‘lonesome Place’ is far more terrifying than seeing a ghostly horseman or an assassin.

We can seek to protect ourselves from some perceived threat lurking out there in the real world – Dickinson neatly invokes such an idea through the thriller-inspired image of arming oneself with a revolver and bolting the door – but to do so is to overlook a far more powerful and dangerous ‘spectre’, or something that is ‘More’ than a spectre, in that it can never be seen and thus will always remain invisible and, to a degree, unknowable. And fear of the unknown is one of the most potent fears.

‘One need not be a Chamber to be Haunted’ is a fine example of Emily Dickinson’s interest in the mind and the demons that can lurk within.

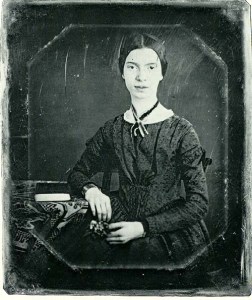

About Emily Dickinson

Perhaps no other poet has attained such a high reputation after their death that was unknown to them during their lifetime. Born in 1830, Emily Dickinson lived her whole life within the few miles around her hometown of Amherst, Massachusetts. She never married, despite several romantic correspondences, and was better-known as a gardener than as a poet while she was alive.

Nevertheless, it’s not quite true (as it’s sometimes alleged) that none of Dickinson’s poems was published during her own lifetime. A handful – fewer than a dozen of some 1,800 poems she wrote in total – appeared in an 1864 anthology, Drum Beat, published to raise money for Union soldiers fighting in the Civil War. But it was four years after her death, in 1890, that a book of her poetry would appear before the American public for the first time and her posthumous career would begin to take off.

Dickinson collected around eight hundred of her poems into little manuscript books which she lovingly put together without telling anyone. Her poetry is instantly recognisable for her idiosyncratic use of dashes in place of other forms of punctuation. She frequently uses the four-line stanza (or quatrain), and, unusually for a nineteenth-century poet, utilises pararhyme or half-rhyme as often as full rhyme. The epitaph on Emily Dickinson’s gravestone, composed by the poet herself, features just two words: ‘called back’.

If you enjoyed this poem, continue your discovery with our analysis of her poem about depression, ‘It was not Death, for I stood up’ and our analysis of ‘I heard a Fly buzz – when I died’. If you want to own all of Dickinson’s wonderful poetry in a single volume, you can: we recommend the Faber edition of her Complete Poems.

The author of this article, Dr Oliver Tearle, is a literary critic and lecturer in English at Loughborough University. He is the author of, among others, The Secret Library: A Book-Lovers’ Journey Through Curiosities of History and The Great War, The Waste Land and the Modernist Long Poem.