One of Dickinson’s best-loved short lyrics: an analysis

‘I’m Nobody! Who are you?’ is one of Emily Dickinson’s best-known poems, and one of her most celebrated opening lines, and as opening lines go, it’s wonderfully striking and memorable. The opening line features in our pick of the best Emily Dickinson quotations.

What follows is the poem, followed by a brief analysis of its meaning and features.

I’m Nobody! Who are you?

Are you – Nobody – too?

Then there’s a pair of us!

Don’t tell! they’d advertise – you know!

How dreary – to be – Somebody!

How public – like a Frog –

To tell one’s name – the livelong June –

To an admiring Bog!

‘I’m Nobody! Who are you?’: summary

The poem may be summarised very simply as being about how it is actually quite nice to be a Nobody rather than a Somebody – that anonymity is preferable to fame or public recognition.

Nobodies can stick together and revel in their anonymity, but it’s more difficult to find companionship and an equal when you’re in the public eye. As the old line has it, it’s lonely at the top.

Rather than buy the other old line – that fame and distinction are unequivocally desirable – Dickinson sees anonymity as an advantage. The poet proudly declares her ordinariness, her likeness to everyone else rather than her uniqueness.

‘I’m Nobody! Who are you?’: analysis

As with all Emily Dickinson poems, though, it is not so much what the poem says as how it says it that makes the poem distinct, memorable, and profound.

The rhyme scheme is erratic: the two stanzas roughly rhyme abcb, as with most of Dickinson’s poems, but this is unsettled right from the start:

I’m Nobody! Who are you?

Are you – Nobody – too?

Then there’s a pair of us!

Don’t tell! they’d advertise – you know!

The rhyme of ‘too’ and ‘know’ is only half-rhyme: ‘too’ looks back to ‘you’ (‘Who are you?’) more than it looks forward to ‘know’ (‘know’ itself picks up on the ‘No’ of ‘Nobody’). The use of the longer word ‘advertise’ among shorter,  simpler words draws our attention to that word, and this is deliberate. Nobody draws attention to Nobodies; but to do so would be to attempt to make them conspicuous, to advertise them, and the word advertise (easily the longest word in the stanza) is itself conspicuous in the poem.

simpler words draws our attention to that word, and this is deliberate. Nobody draws attention to Nobodies; but to do so would be to attempt to make them conspicuous, to advertise them, and the word advertise (easily the longest word in the stanza) is itself conspicuous in the poem.

How dreary – to be – Somebody!

How public – like a Frog –

To tell one’s name – the livelong June –

To an admiring Bog!

The rhyme scheme in the second stanza is more conventional (Frog/Bog), but the imagery is enigmatic. Why is a ‘Somebody’ like a frog? Because it croaks its (self-)importance constantly, to remind its surroundings that it is – indeed – Somebody? Or because there is something slimy and distasteful about people who possess smug self-importance because they are ‘Somebodies’.

Indeed, the clue lies in that opening line, which, if it is read as a response to a question (absent from the poem), makes more sense. But what question?

The one that fits the bill is Who do you think you are? or Who the hell are you? Dickinson’s opening line, and the question shot back at the unseen addressee, support such an idea.

This would explain the uneasiness of the rhyme scheme in the first stanza: the poem can also be read as satirical. In this reading of the poem, Dickinson’s speaker does not identify with the addressee of the poem, because the addressee – unlike Dickinson herself – is deluded and believes himself to be a Somebody. Dickinson pricks this pomposity and, with faux innocence, pretends to identify with another self-confessed Nobody.

Another haughty question, often asked by a supercilious Somebody, is Don’t you know who I am? Dickinson knows she is a Nobody; the problem is that this other person doesn’t realise that he himself is also a Nobody.

Ultimately, Dickinson’s short lyric can be read either as a straightforward celebration of ‘Nobodiness’, of being that overlooked and underrated thing: the face in the crowd.

But it also allows for a more cunning satirical reading, whereby the poem is imagined to be a response to a question that has been left out of the poem. The strength of this poem is that it can be analysed either way – often the mark of great poetry.

However, there may be a third way of interpreting the poem, which is to see it as satire, but satire which mocks those sentimental devotional poets of the nineteenth century who praised the natural world and the heavens while humbly downplaying their own significance: next to the grandeur and majesty of the heavens, or the beauty and wonder of a mountain or an ocean, the sheer vastness of the world, how important is the individual human?

There were plenty of sentimental poets in nineteenth-century America writing such verse: showing off how wonderfully humble they were, if you will. Is Dickinson satirising them in ‘I’m Nobody! Who are you?’ Perhaps.

But more importantly – and perhaps more persuasively – the poem reflects Dickinson’s own suspicion of the limelight, and her fondness for privacy over celebrity. Famously (as it were), in her own lifetime, she was known more for her gardening than her poetry.

About Emily Dickinson

Perhaps no other poet has attained such a high reputation after their death that was unknown to them during their lifetime. Born in 1830, Emily Dickinson lived her whole life within the few miles around her hometown of Amherst, Massachusetts. She never married, despite several romantic correspondences, and was better-known as a gardener than as a poet while she was alive.

Nevertheless, it’s not quite true (as it’s sometimes alleged) that none of Dickinson’s poems was published during her own lifetime. A handful – fewer than a dozen of some 1,800 poems she wrote in total – appeared in an 1864 anthology, Drum Beat, published to raise money for Union soldiers fighting in the Civil War. But it was four years after her death, in 1890, that a book of her poetry would appear before the American public for the first time and her posthumous career would begin to take off.

Dickinson collected around eight hundred of her poems into little manuscript books which she lovingly put together without telling anyone. Her poetry is instantly recognisable for her idiosyncratic use of dashes in place of other forms of punctuation. She frequently uses the four-line stanza (or quatrain), and, unusually for a nineteenth-century poet, utilises pararhyme or half-rhyme as often as full rhyme. The epitaph on Emily Dickinson’s gravestone, composed by the poet herself, features just two words: ‘called back’.

Emily Dickinson’s Complete Poems is well worth getting hold of in the beautiful (and rather thick) single volume edition by Faber. We’ve also discussed another of Emily Dickinson’s most famous poems, her poem about telling the truth ‘slant’, and we discuss ‘Hope is the thing with feathers’ here. Continue your American poetry odyssey with our pick of the best American poems.

For more tips on how analyse poetry, see our post offering advice on the close reading of a poem. If you’re revising for an exam, you might find our post on how to remember anything for an exam useful. Continue to explore American poetry with our analysis of the classic Wallace Stevens poem, ‘The Emperor of Ice-Cream’. If you’re studying poetry, we recommend checking out these five books for the student of poetry.

The author of this article, Dr Oliver Tearle, is a literary critic and lecturer in English at Loughborough University. He is the author of, among others, The Secret Library: A Book-Lovers’ Journey Through Curiosities of History and The Great War, The Waste Land and the Modernist Long Poem.

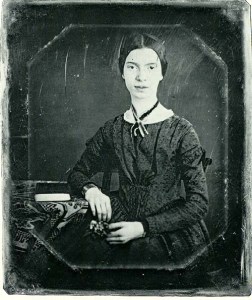

Image: Black/white photograph of Emily Dickinson by William C. North (1846/7), Wikimedia Commons.

Discover more from Interesting Literature

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

Reblogged this on nativemericangirl's Blog.

This is such a lively poem. I was wondering though, why does Dickenson use dashes so often?

There are numerous theories for this, but the honest answer is that we don’t really know! It certainly makes for a very distinctive style – telegrammatic and idiosyncratic – as Wendy Cope notes in her poem: https://theartofreading.wordpress.com/2010/11/17/emily-dickinson-by-wendy-cope/

Thank you for explaining and the link.

Dash it all, Emily, your swift insights into human nature are enigmatically pleasing

Emily, understood well, that celebrity is a contradiction. All those that are really great don’t want celebrity, because celebrity hurts the sensitive feelings of the poet.

I just read this poem an hour ago and here we are with this. What a coincidence :)

When I did the MOOC – Modern American Poetry – the close readings of Emily Dickinson were a revelation. If anyone is interested I’d highly recommend the course! Many of hers seemed opaque on first reading – The Brain Is Wider Than The Sky is one of my favourites.

Great analysis of my favorite Emily Dickinson poem!

Thank you!

Reblogged this on Jude's Threshold and commented:

On dear Emily!