A short and interesting history of Magna Carta and its surprising legacy

So few of the facts about Magna Carta in popular circulation are true. Its enduring place in popular consciousness is, however, indisputable. Its influence even extends to music: Kurt Weill composed a cantata, The Ballad of Magna Carta, about it. The rapper Jay Z even named his twelfth album after Magna Carta (albeit more because of a pun on his real name, Carter, than because he is a fan of the document, we assume). In this post, we’ll seek to debunk some common myths about Magna Carta and discuss some of the most interesting facts about it.

Magna Carta wasn’t the first such charter: a century before, Henry I of England had issued a coronation charter in 1100, comprising 20 clauses. Yet it was Magna Carta that lasted in the English – indeed, the world’s – memory. The story of disgruntled barons forcing King John to sign a charter that would provide them – and other Englishmen – with liberties and rights that the tyrannical king had denied them is part of English folklore, bound up with the tales of the valiant Robin Hood countering John’s brutal rule by stealing from the rich and giving to the poor. (Though as we discussed in our Interesting Facts about Robin Hood, this is a later myth and the original story of Robin Hood was quite different.)

And we all know where and when King John signed Magna Carta: ‘Runnymede, in 1215.’ Except, in fact, that he didn’t sign it – not in the modern sense of the word ‘signed’, anyway. As was the norm with royal documents and legal agreements made with rulers at the time, John signalled his agreement to the document (with his fingers crossed behind his back, one suspects) by setting his seal upon Magna Carta.

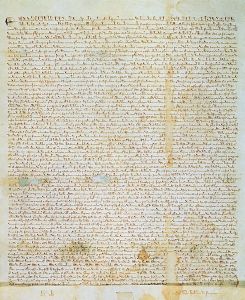

The document comprises some 3,550 words, written in Latin, the language of the law throughout the Middle Ages. Parts of the document appear quaint and are entirely irrelevant now, such as the clause about the removal of fish weirs from the Medway and the proper width for the bolts of cloth used in the making of monks’ robes.

It was only called ‘Magna Carta’ later on, in 1218, not at the time when it was drawn up. Not only that, but the original charter which was sealed by John was only valid for a short period – a few months – and wasn’t intended as a  perennially binding legal document. (And indeed, as we’ll discuss in a moment, it has proved to be anything but.) The famous numbered sections were a later addition, too: the original text was an unbroken, continuous stream of demands and assertions.

perennially binding legal document. (And indeed, as we’ll discuss in a moment, it has proved to be anything but.) The famous numbered sections were a later addition, too: the original text was an unbroken, continuous stream of demands and assertions.

One of the most curious facts about Magna Carta is that, in so far as Magna Carta is celebrated for its enduring importance in English law, we should look not to 1215 at all, but to 1297 when parts of the original 1215 version were restated and made official statute for the first time, during the reign of Edward I. So, if we’re celebrating Magna Carta as a legal document, the 2015 octocentenary is, we’re sorry to announce, a little premature – 82 years premature, to be precise. The 1215 Magna Carta was almost immediately repudiated by John, before the wax seal had even dried, and he appealed to the Pope to declare it null and void. If Magna Carta‘s perpetual presence in English – indeed, world – consciousness is down to a King of England, it is arguably Henry III, John’s son, who should get the credit: in 1225 he embraced the charter which his father had rejected. (Henry himself would later be forced to put his name to a charter of ‘rights’ demanded by barons, when Simon de Montfort and his followers drew up the Provisions of Oxford in 1258 – often overlooked, this document was at least as important as Magna Carta in English legal and constitutional history.)

But in fact, we probably shouldn’t hold up Magna Carta as the paragon of British lawmaking at all. The official ‘gov.uk’ page on the Magna Carta illustrates just how little of the Magna Carta – even that 1297 Magna Carta – remains enacted in British Law: just three articles from the charter are part of UK law. Of these three, only one, clause 29 (based on chapters 39 and 40 in the earlier document, though the numbering was a later addition), is widely known (the other two concern the Church and the liberties of the City of London). That is the clause or article which states: ‘No free man shall be seized or imprisoned, or stripped of his rights or possessions, or outlawed or exiled, or deprived of his standing in any other way, nor will we proceed with force against him, or send others to do so, except by the lawful judgment of his equals or by the law of the land.’ But this didn’t include everybody. Indeed, it ruled out half the population of England at the time, the half who were not ‘free men’ but villeins or serfs owing fealty to their lord.

As David Allen Green puts it in his excellent Financial Times blog post on the subject, ‘In modern Britain, Magna Carta has all the legal and political force of an answer to a Trivial Pursuit question.’ Yet Magna Carta has endured in the popular consciousness – as a name, as an idea, as a symbol. It was first printed in 1508 (as a book so small it could fit into your palm quite comfortably). And it is prized not just in Britain, either: at his trial in 1964, Nelson Mandela cited Magna Carta as one of the icons of western democracy. Fittingly, the John F. Kennedy memorial – the only piece of American soil in England – is at Runnymede, where Kennedy’s kingly namesake had sealed Magna Carta over seven hundred years before.

In 2007, a copy of the 1297 Magna Carta sold at auction for $21.3 million – the most that has ever been paid for a single page of text.

If you enjoyed these interesting facts about Magna Carta, you might also enjoy our other posts on medieval loveliness, especially our 10 Short Medieval Poems Everyone Should Read.

Image: The 1297 version of Magna Carta, Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

Discover more from Interesting Literature

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

Hi,

I learn so much from your blog! I love it! You fan and lots of love, Emily

Reblogged this on JamesLordsBlog and commented:

misrelated history for the common man and woman of our time. in ignorance may we play…..

Reblogged this on Our Days & Futures.

Reblogged this on Beechdey’s Weblog.

Reblogged this on Elena Falletti.